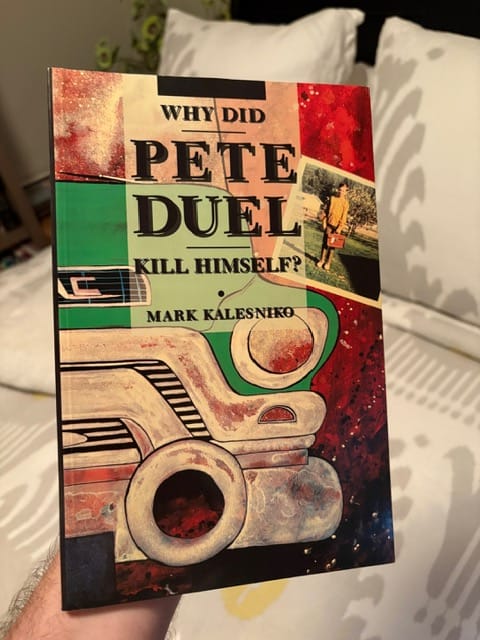

My Canon: Why Did Pete Duel Kill Himself? by Mark Kalesniko

The first time I read Why Did Pete Duel Kill Himself?, I didn't know Duel was a real person until the book's end. I can't fully explain why that elevated a great comic to one I end up reading every time I'm home in California and my copy is nearby.

Why? is a quick 87 pages and it reads even faster than that number might imply. This is notable because Kalesniko released it through Fantagraphics in 1997 and his next three books/collections, also put out through the publisher, ran 264, 250 and 416 pages. Especially compared to other comics, those books are massive. They're all at least partly autobiographical, though Kalesniko's stand-in is an anthropomorphic dog named Alex who lives in our regular human world and whose dogness is never commented on. There's a lot going on in those other three books.

The most recent one, Highway, covers Mark/Alex's time as a Disney animator and follows the big moments and attendant feelings of at least a decade of his life. Why? goes in a few directions, but each leads to the same places: shame and maturity.

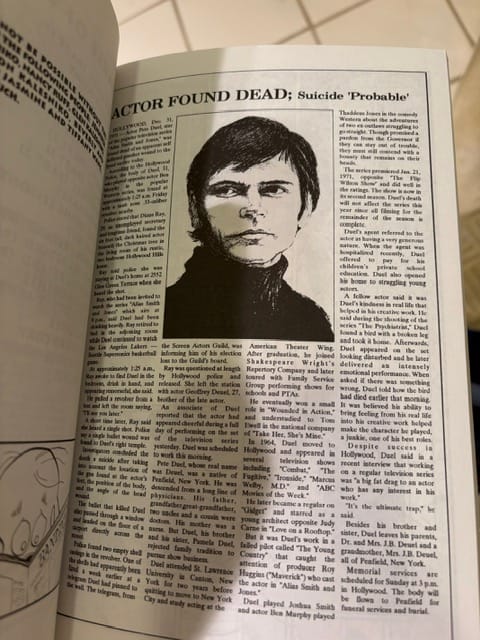

If you, like me, were unaware, Pete Duel was most famous as an actor on the TV Western Alias Smith and Jones, He played Smith for 33 episodes before killing himself.

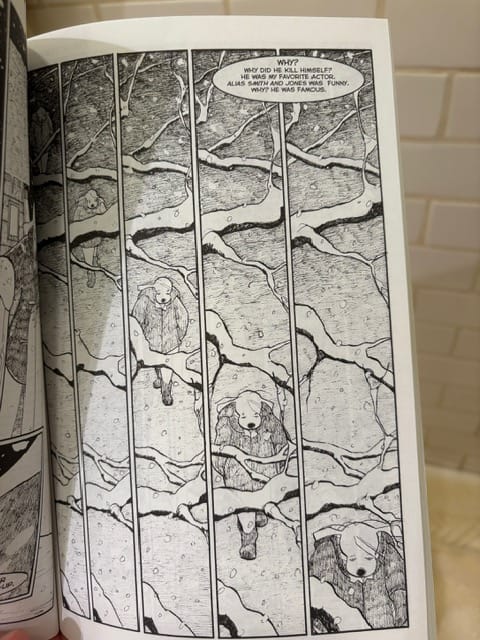

There are no answers to the title question, which elementary school-aged Alex wonders after hearing the news. Kalesniko doesn't draw reenactments of scenes from Duel's life and he doesn't speculate on anything physical that would have happened behind closed doors. The parts of the book that try to answer that question are all speculation, from a child's perspective, of why Pete Duel, one of Alex/Kalesniko's favorite actors, would kill himself.

There is no answer, because Mark Kalesniko is not Pete Duel, but the reason for asking the question is illuminated in a separate thought:

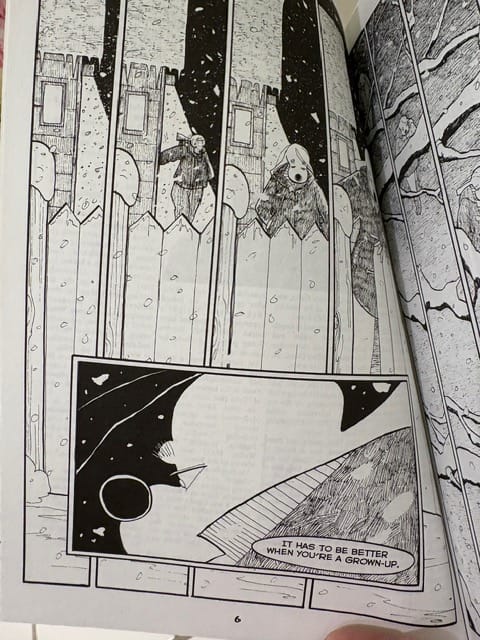

"It has to be better when you're a grown-up."

In Spike Jonze's short documentary What's Up, Fatlip?, released when the rapper re-emerged with a solo album ten years after being kicked out of The Pharcyde, Fatlip reflects on his life at 36: "You think, maybe this is it, maybe I'm going to be stupid forever."

I'm 36 now and have been struggling for at least a decade with the worry that I'm going to be stupid forever, that I need to start actively becoming a better person soon, because it's not going to happen to me in one spontaneous moment. But I remember the feeling Kalesniko has his avatar express here. I felt it plenty of times: I was younger and things were confusing, but someday, I assumed, they would make sense. Someday I'd fall in love with a person who loved me, someday my interests would coalesce around an itemized list of marketable skills, someday I'd live on my own and make the rent. These things have happened or have not happened to varying degrees. I'm in a wonderful relationship with a person I love, for example. I can't take that away from myself. But it feels, as I'm sure it does for you, that some things have never clicked as I thought they would. I am probably less able to gracefully mesh with a roomful of strangers now than ever before. I am bad with money. I can't keep in contact with people.

To a kid, introducing the idea that a person could be so depressed they'd prefer life stopping to any alternative is terrifying. I'm never going to kill myself, but I don't think suicide as an option is what terrifies Kalesniko's character anyway. I think it's just the possibility of things not getting better, or the linked possibility that things getting better will not be enough.

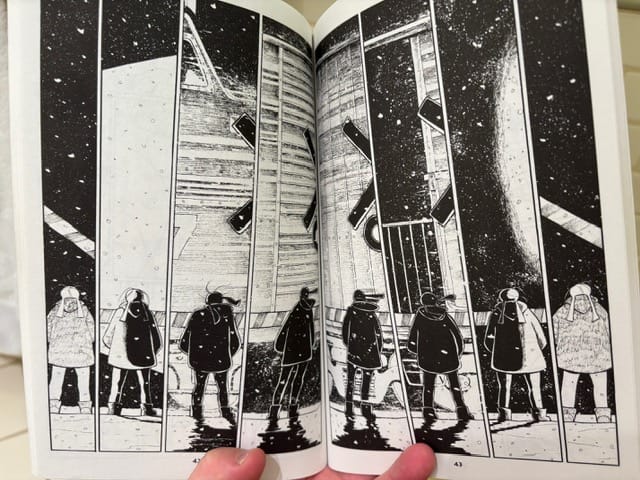

Much of the book is laid out as the two pages I've shared are: a single thought over a few panels of movement. That's how the book feels: a long, slow walk, on which you consider whatever comes to mind. The physical brevity of the work helps: you recognize the feelings without feeling them for too long yourself. If you felt them, it'd barely be art. It might just be masturbation.

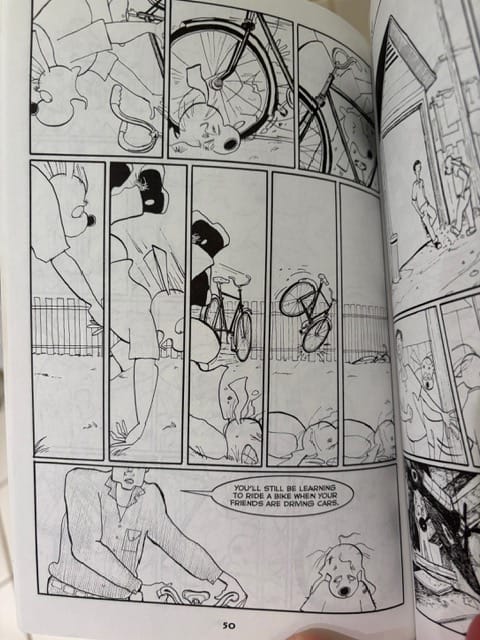

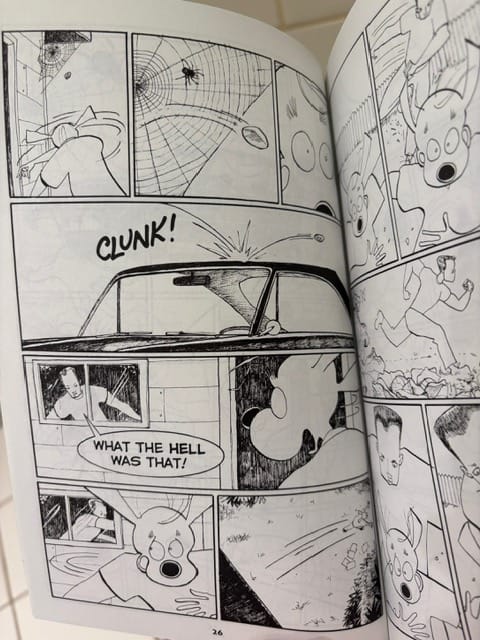

The other parts of the book are rough memories, the memories that slingshot to the foreground without notice. These are the kind of memories that will make me wince while reading a completely unrelated book, and my wife will ask what's wrong and I'll say, mostly truthfully, "nothing." This section hits hard, even if you can't relate, though I promise you can. It reminds me of Wayne Koestenbaum's Humiliation, where the author both writes an essay about that feeling and then digs deep into past shames in such a way that would command empathy from a Republican.

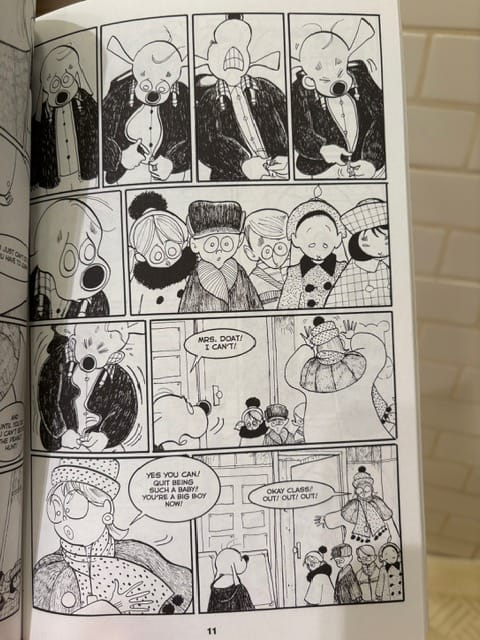

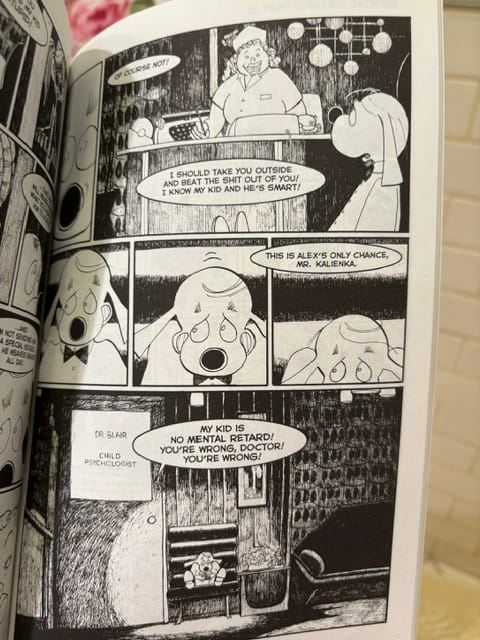

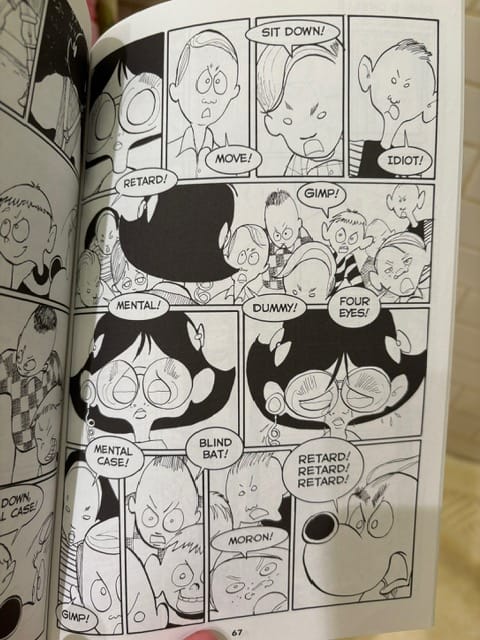

There are two settings for these memories. One is at home, with a quick-to-anger dad. I've included two examples of those, above. The other is at school, with teachers and classmates who don't fully understand Alex. I've included two examples of those, below.

In the first scene here, Alex is unable to zip up his jacket and is called a baby by his teacher. In the second, a fusion of the two types of memories, Alex sits in a hall at his school as his father loudly insists his son won't be placed in a special education program.

The reason this book is really something special comes later, when Alex remembers joining in with other kids as they torment a classmate. They call her "mental," "idiot," a "gimp" when she can't answer a question. She has thick glasses and a hearing aid. It isn't her fault, not that it ever could be anyway. And Alex repeatedly calls her a "retard."

Because this is not a self-pity catalog. It is not a photo album of times a person was wronged by the world. Alex is doing to an innocent what others have done to him and he's doing it to get a leg up on them to maybe no longer be one of the people who gets made fun of. Everybody gets damaged. Everybody damages. If the little girl grew up to write her own Who Killed Pete Duel?, this scene would be in her book, too. It might look identical to the page in Kalesniko's version.

So there are no answers to the title question, but there is perhaps some peace in continuing to ask it. Do things get better when you're an adult? Maybe. We don't see enough of Alex's life to know Kalesniko's answer to that question. But the fact that he's alive means that even if Alex knows why a person would kill himself, even if he's felt the same way, he hasn't done it. That's victory. Kalesniko is still alive, too. He wrote and drew a number of excellent books after this one. This does not make Duel a loser and thinking of him doesn't evoke any feelings of shame. This could all run parallel to a victory/loss binary and have nothing to do with struggle. I don't really care. But it means something that the Alex character is still alive.

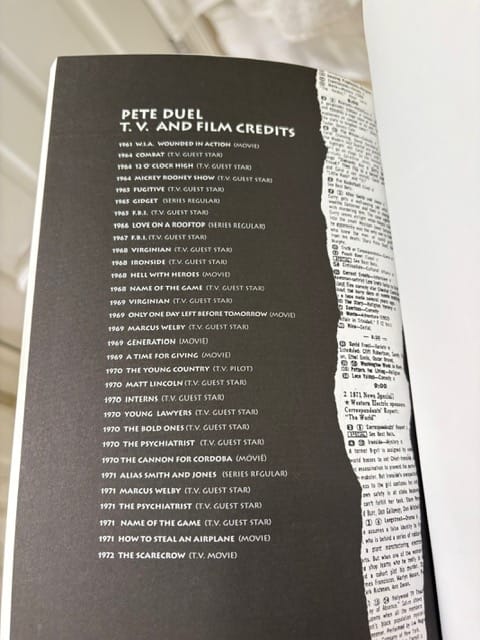

Why? ends with Duel's filmography and an obituary. I don't know if the obit was taken from an actual contemporaneous newspaper or if it's something Kalesniko himself wrote. Either way, the message is the same: Pete Duel is gone, but he meant something.

I don't like that I'm still asking some of the questions Kalesniko was asking in 1997. I'm glad I'm around to ask them, though. Do things get better? Sure. I'm writing something and you're reading it. That's pretty special all on its own. Thank you.